Network Analysis to Understand an Object's Sentimentality in Context

Network Analysis to Understand an Object’s Sentimentality in Context

How do connections between an object and its context affect the sentimentality between a person and an object?

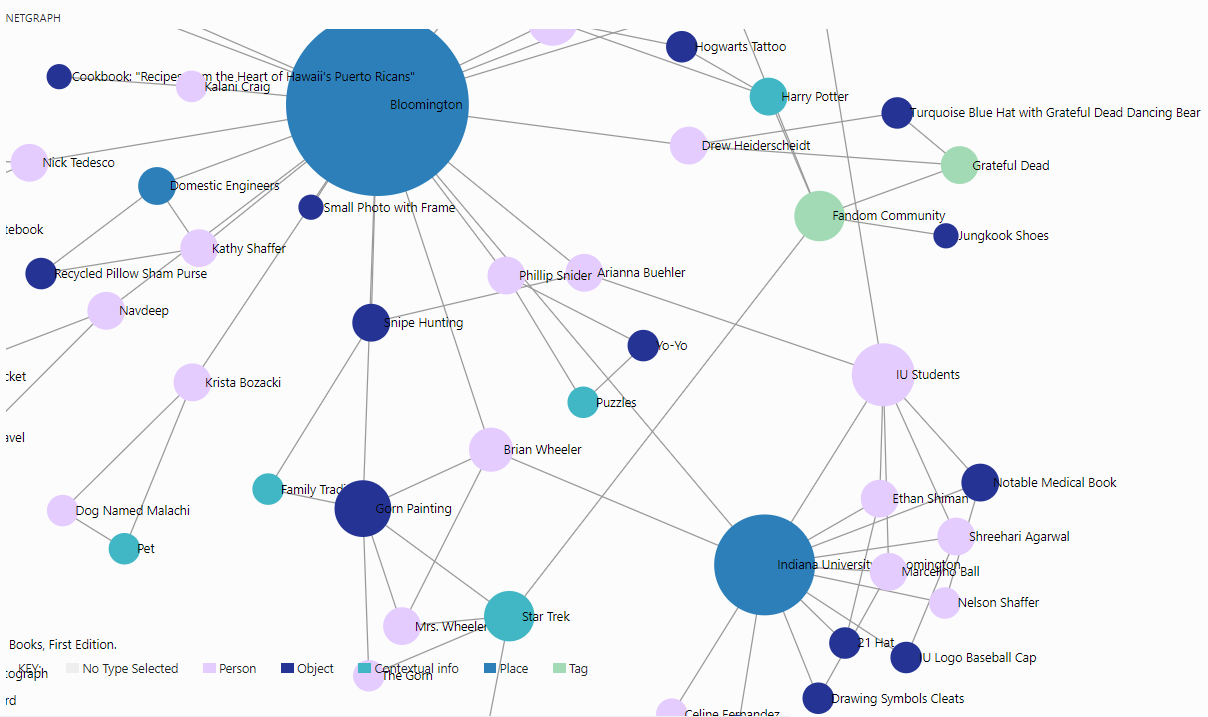

Our items all inspire a sense of sentimentality from the contributors. Some have a cultural connection, like the kimono and baby blankets, while others are more related to individual expresssion and family ties like the cleats and Gorn painting, respectively. Our network is allowing us to see how objects originating from different cultures find their way to a specific location.

Using Network Analysis to Understand how Sentimentality affects Objects and their Cultures

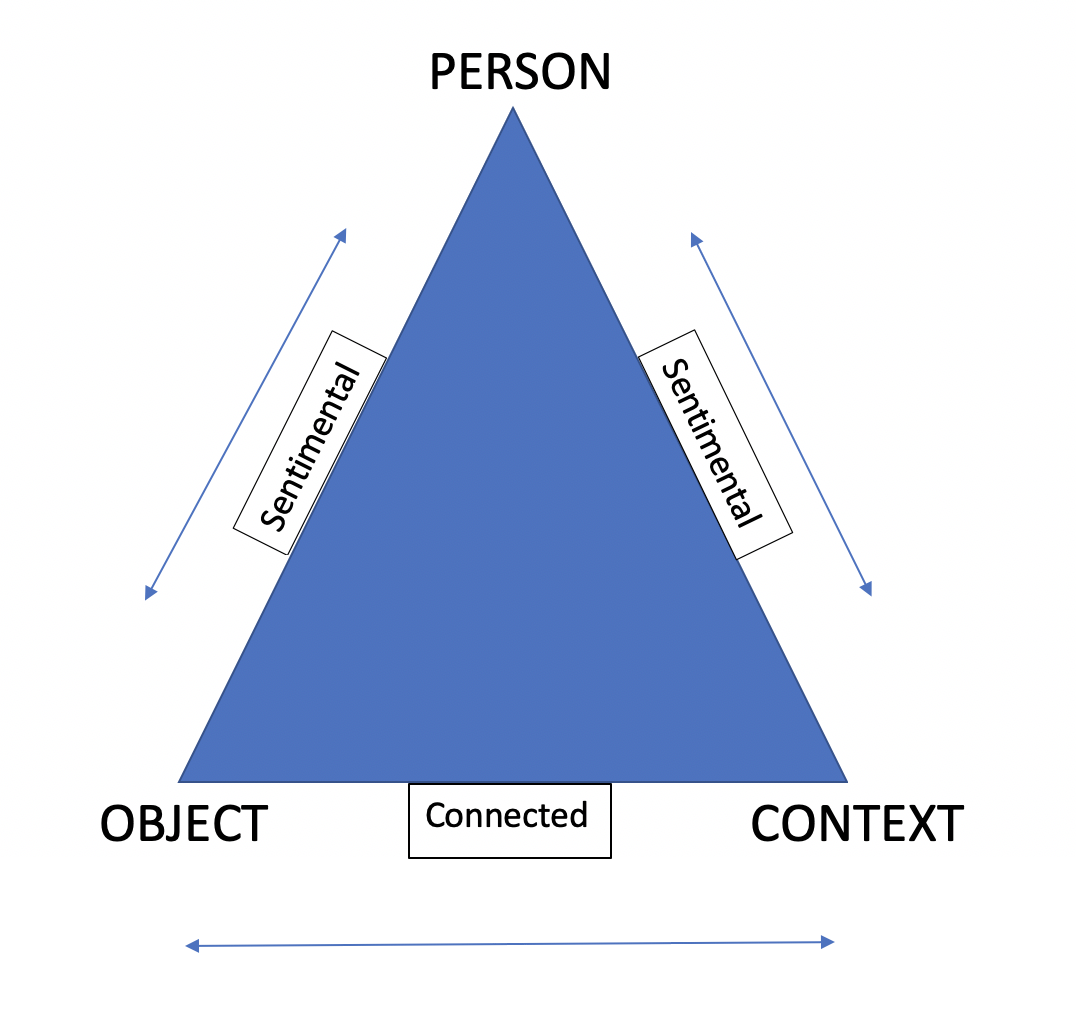

We created a base model on a blackboard (digital recreation shown above) depicting how we were going to link our objects, their contributors, and their significance together, and see how they would all connect to a larger sense of community here at Indiana University. Using this model, we were able to see how seemingly different objects all came together here at Indiana University, from their different cultural backgrounds and different locations around the world. This led us to divide our objects based on their cultural context, individuality, and/or location of origin. Not all of the objects fell into all three of the categories, some only fell into one.

In “Kinkeeping and Caregiving: Contributions of Older People in Immigrant Families”, Judith Treas and Shampa Mazumdar discuss the way immigrants, among other established groups in the U.S., work to build community. The connected objects can show different manners in which people establish community, as many of the objects are tied to family, community, or culture. Andrew McKevitt explains this beautifully by stating that “Historians can use examples of… foreign products and practices to draw tentative conclusions about the ways in which cultural globalization has tansformed the United States.” He further explains that people who create and embrace more “organic” ways of exploring their cultural heritage, or objects that tie them to a certain culture or community, that are free of the influence of govermental, corporate, and non-governmental organizations, have allowed the true cultural globalization of objects to find their way either to the United States themselves, or the culture itself to come to the U.S. and influence the creation of the objects here.

Further described in Treas and Mazumdar’s work is the role immigrants play in their families, with them often caring for their children and having active roles in their lives. One way in which immigrants can have roles in their families’ lives is through the giving of gifts, such as Nana’s Cobija. This role is reflected even in the gifts given by non-immigrant Americans, such as the Gorn painting and Kimono. A number of nodes on the network analysis display a trend of contributed items being gifts from family members, suggesting that the relation to family is a notable factor in forming sentimentality.

In her work “Lining, Testifying, and ‘Blackenizing’: The Musical Expression of Black American Church Families.”, Thérèse Smith notes the importance of black churches in their communities and establishes that family ties are not needed to establish community. This is reflected in objects such as the pillow sham bag, where a local club was the source of community, and the Grateful Dead hat, where a shared love for the band created community. This latter source, fandom community, is a major influence reflected in the network analysis. With the advent of the internet, people can connect and form communities in online spaces, allowing for a new outlet separate from family, and a connection that spans worldwide in a new way.

The Gorn Painting for Brian Wheeler seems to represent not only family, but a love for the Star Trek fandom. However, the connection is much greater than that. The painting establishes a small community between Brian, the painting establishes a small community between Brian, the painting, and his mom. In her article “Star Trek Lives: Trekker Slang”, Patricia Byrd discusses how a community of fans has established to a point where they have their own “language” of sorts, mixing and combining Star Trek terms in a way that only certain people could decipher and understand. The community stretches world-wide and serves to expand the community the Gorn Painting creates and represents. While it has a personal community, it also has a world-wide cultural community as well. The ability to take an object and expand its brand into a larger area allows us to draw connections we might not originally identify upon first glance. Every object has a personal community as well as a larger, culturally encompassing one.

Once can see this in other harvest objects, including the kimono, blanket, and cleats. All have a special personal relation with their owner and their creator. However, they all have a larger community that helps identify them with an aspect that ties relations to cultures all over the world. For the kimono comes a Japanese relationship, for the blanket comes Mexican heritage, and the cleats, while coming from a more American culture, still show ties to both family and other symbols of American culture. This is crucial for understanding the full history of an item for recognizing and understanding it on a focused level and a broad one.

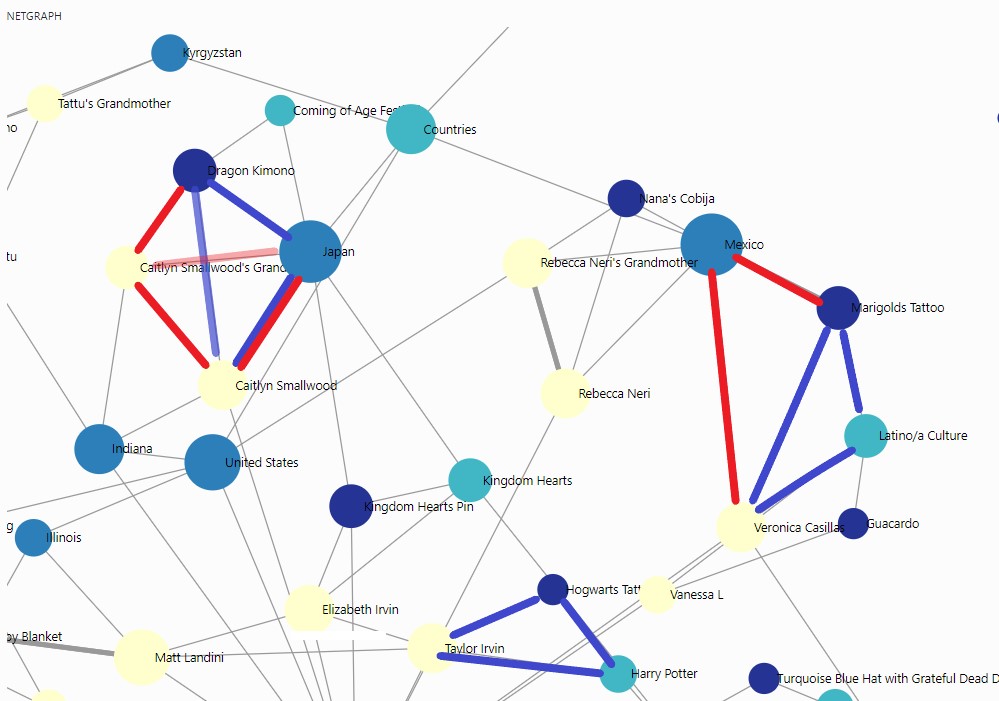

If we use McKevitt’s observation of cultural globalization, combined with our network analysis, we can start to see how our Blackboard Model not only shows us these connections between person, object, and context for our four objects represented on this page, but how the model tends to hold true for all the objects that we were able to collect. If we compare objects like the kimono, the marigold tattoo of Veronica’s, and Taylor’s Harry Potter Tattoo, we can see that they all have a different connection between the context and the object, but all three represent a bond of sentimentality that holds the person connected to the object and the context, and then some third bond that connects the object to the context. The kimono’s is the bond between it, Japan, and the fact that Caitlyn and her grandfather are the only two in their family to share that experience, even though their trips to Japan were separated by a generation. Veronica’s marigold tattoo’s bond between the tattoo and her Latina culture is represented in the meaning behind the marigolds themselves: a flower used in their culture to guide the spirits to their respective shrine. They also have another representation of strength and survival, something that signifies another part of her journey. Lastly, if we look at the Hogwarts tattoo that Taylor allowed us to capture, we can see this connect between a love that he has had since childhood for a series that has been an escape for him, combined with his love for tattoos, and the representation of what Hogwarts means to the world of Harry Potter. You can see these connections below. The blue lines represent the connections between the person, their object, and the “context” that their object and themselves share. The red shows the background that their object either has, how it came into their possession, and/or how it gives more sentimentality to the connection between them and their object.

The other marvel that examples like these give us is that we can “see” through our network analysis the cultural globalization that McKevitt describes. Our connections and our theory of our model allow us to see just how all these different cultures, both domestic and international, can make their way into one community. Also, we have the chance to dive into the depths as to how they made their way into not only their respective owners procession, but also into said community. We have been able to physically connect how Harry Potter, Mexican culture, and Japanese culture all made their way into Bloomington. We have been able to see how a recipe book from Hawai’i and a necklace from parents in China give such a personalized meaning to an individual, despite them being viewed as either “mass-produced” or every-day common objects.

The first World Cup held in Africa and the cultural expression that accompanied it fits with many other items within our network. This source described the expression and communalism that was established by the African players and citizens at the event. The authentic and original African garb and colors that they wore allowed them to express themselves on a national stage. This connects extremely well to the Dragon Kimono observed in the network. This kimono is a perfect example of a culture expressing themselves through individual, one-of-a-kind apparel. Marigold’s tattoo in the network is also an unbelievable example of someone being able to represent her latino/a culture through expression on her body. Individualism and sentimentality through apparel, or clothing, or dress can be found throughout the entirety of the network.

Viewing our Network in a Geographical Space

Another interesting thing that we can see with this network is what happens when we, thanks to our instructor Prof. Craig, had all of our objects, people, places, and context placed into a geographical space. If we look below, we can see that a LARGE portion of the objects and people have a centralized location either in, or around, Bloomington, Indiana. When we compare this to the network itself, we can see that Bloomington is the largest node, meaning that it has the most connection, or edges, to it. However, where this map gives us its full use is when we have the chance to see the nodes that are spread further away from Bloomington itself.

Yes, there are some nodes located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and yes, they are supposed to be there. This is where this map really starts to shine. We can see from our network that our model of person, object, and contextual information all hold true, but we do not get to see the cultural significance in a physical space that the network holds. If we take those nodes that are in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, those show us that those people and/or their objects have significance in multiple locations or cultures. This dual-cultural/locational placement, shown by the edges in the network, allows us to see how this object and people have both a connection to their home country, the objects country of origin, or the origin of their culture, and the physical location that they and/or the object reside in today. This can also give us another level of that sentimentality connection that we set out to research before we started creating this network in October of 2019. Being able to see that, for example, Caitlyn Smallwood, is floating somewhere in roughly Israel (somewhere she has never been) may not look significant. However, what it shows us instead is that she has a split significance between being here in Bloomington, Indiana, and in Japan, where not only she had visited as a teenager, but her grandfather served in World War II and brought her back the dragon kimono that she brought for our History Harvest. If we then go from her to her grandfather, who also resided in Indiana, we can see that he is connected even closer to Japan than to Bloomington. This shows us that Caitlyn not only has another connection closer to where they both traveled to, but that her grandfather had a closer connection to Japan than to Bloomington. This, of course, is all in relationship to Japan and the dragon kimono he gave to Caitlyn, not a representation of his life being more rooted in Japan. Lastly, we have the chance to see that people have connections to a culture regardless of whether or not they have physically been to a place that is home to that culture or not.

Our Network Broken Down in Factions

This faction analysis separates the network analysis into groupings, which are denoted by color. These groupings display similarities in certain objects and paint a picture of the major sources of sentimentality felt by the contributors. Notably, despite there being separate groups, certain nodes blend between them, emphasizing that they aren’t exclusive and can represent many things to contributors. Such examples include Brian Wheeler at the crossroads between Indiana University and Fandom Culture and Veronica Casillas between Bloomington and Mexico.

The most prominent groups include Indiana University, Bloomington, Mexico, Japan and Fandom Culture. The Indiana University group shows multiple ways in which individuals can become attached to the university, whether it be through sports or local communities. In a similar vein, Bloomington shows the different origins of people whose sentimentality is connected to the town at large. For example, Kathy Shaffer and her recycled pillow sham purse originate from Bloomington and have an attachment to the town that isn’t related to the University. In contrast, Philip’s object was one he found himself attached to over the course of his first semester at IU.

A major source of sentimentality reflected in the Japan, Mexico, and Fandom groups is that of community. The Fandom group shows the common interests that bring people together. Notably, the interests represented don’t originate from Bloomington, but from elsewhere, and it’s the shared enjoyment that gives the object its value. For example, Brian Wheeler had an inside joke with his family about an episode of Star Trek, and a painting of a scene from it by his mother provided him with a sense of community.

Japan has a unique connection to fandom culture through Kingdom Hearts. Additionally, it’s represented by a kimono, which was given to the contributor by her grandfather during a visit and was used for a coming of age festival. This serves to show that different aspects of a country’s culture can be influential in the development of sentimentality. Mexico is represented similarly. While Rebecca Neri has her connection to Mexico through her grandmother, a broader Latino culture is what connects contributors such as Veronica and Vanessa to the country, adding a sense of identity to the mix. The prominence of family across multiple different groups shows that despite interests and origins, connections to family is a major source of sentimentality.

Connecting Everything to our Research Question

Network analysis allows the ability to illustrate a visual connection between an item and its correspondents, whether that is an owner, creator, or even a contextual event. The links between an item and its related nodes help to show a deeper connection, describing how an object has a significant meaning beyond its surface. By linking nodes to other nodes, one is able to see how objects that appear unrelated actually have underlying backgrounds that tie them together. We created a model to base all objects off of, forming a connection triangle between a person, an object, and the context of the object. For our group, we did research on a painting, a kimono, a blanket, and a pair of cleats – all seemingly unrelated and mutually exclusive at first glance. However, after applying our network analysis triangle model, we were able to see the connection between objects via cultural and artistic significances. By tying our object to a context and relating that context to a person’s sentimentality, we were able to form a deeper meaning for objects and then have the ability to link objects with similar contextual values in order to build a web of inter-related connotations. This allowed us to not only interpret and connect our personally chosen objects, but see if there was a similar connection between the other items collected in the history harvest. By linking objects to each other through sentimental context and other factors, we are able to create a community of people and objects that would originally never be placed together.

Referances and Further Readings

Byrd, Patricia. “Star Trek Lives: Trekker Slang.” American Speech, vol. 53, no. 1, 1978, pp. 52–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/455340.

Larlham, D. (2012). On Empathy, Optimism, and Beautiful Play at the First African World Cup. TDR (1988-), 56(1), 18-47. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41407127.

MCKEVITT, ANDREW C. ““You Are Not Alone!”: Anime and the Globalizing of America.” Diplomatic History, vol. 34, no. 5, 2010, pp. 893–921. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24916463.

Smith, Thérèse. “Lining, Testifying, and ‘Blackenizing’: The Musical Expression of Black American Church Families.” Irish Journal of American Studies, vol. 7, 1998, pp. 55–78. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30002407.

Treas, Judith, and Shampa Mazumdar. “Kinkeeping and Caregiving: Contributions of Older People in Immigrant Families.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 2004, pp. 105–122. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41603919.

Featured artifacts in this exhibit: Network analysis to understand an object's sentimentality in context

Nana's Cobija

Rebecca Neri

Pair of blue, yellow and white crocheted blankets, one larger than the other.

Drawing Symbols Cleats

Marcelino Ball

Candy-striped, spiked cleats with broken hearts on the outside painted in black. Adidas three-stripe logo has been painted gold.

Dragon Kimono

Caitlyn Smallwood